~Francois Truffaut

To hear Sam Fuller talk is to know what his films are like. First off, he's the roughest, gruffest Jew you'll ever see. A sizable cigar perpetually inhabits his mouth, yet his speech is unobstructed. He speaks with the certainty of a man who isn't going to stop to hear anyone contradict him. A fine oral storyteller, he knows what makes an interesting story, how to strike the right tone at the right time, follow through with the perfect gesture; and not only that, but his style has such bravura, such pure energy and intensity, that the desire to listen is irresistible.

That his films seem like a manifestation of his personality can only be a good thing. Not merely a manifestation either, but an enhancement, or a dense focus of that energy. This vigorous storytelling he infuses with a mythological essence. His films resemble myths in every way: they have moments of rare and strange beauty; characters who at once express an indefinable humanity and an epic grandeur; complex worlds composed of archetypal landscapes (projections of the characters' mental terrain?); and that mythic voice capable of telling such powerful stories with such a simple form.

While Shock Corridor bears all the familiar traits of a Fuller film (everything mentioned above, as well as moments of great emotional and physical intensity, political commentary, and a shade of B movie pulp), it strikes me as Fuller's most surreal and oneiric; all of his films (that I've seen) have traces of that, but this one has an abundance. Of course, setting the film in an asylum lends itself to such an approach, but Fuller manages to work with that boon without cheapening anything. The core of the story is simple, the whodunit plot and the political allegory, but strange moments and startling dream imagery weave through that core so thoroughly that they become indistinguishable from one another. Fuller's choice of imagery and characters elevates the film beyond simple understanding; the emotional grip of the film affects me in a way I can't quite define (its active, brutal power in the madhouse reality and the passive yet intrusive sway of the more somber moments).

Take, for instance, the characters. We have the three witnesses, of course, all of which are remarkably interesting and charged with political undertones (I say undertones, but I could just as well say overtones). They all have some particular nuance that left an impression. For Stuart, although his self-appointed Civil War hero role is entertaining, it's his moment of clarity: the history he reveals, compared to what we'd seen so far, came as an unexpected jolt, profoundly moving and played with earnest. Watching him revert back to his role of Civil War hero, I felt a strange sadness.

For Boden, the genius/child, it's the state he chooses to return to. And the reaction Barrett has to the portrait Boden drew for him: holy crap. But I love the idea there, becoming afraid of your own identity. . . or whatever Boden drew.

And Trent. For most, I imagine, the most memorable part of the film. His (Hari Rhodes) performance is astounding, full of frightening power, and his force only adds to the strangeness of the circumstances. And is it strange. The image of him in the pillowcase Ku Klux Klan mask, orating before he chases the old black man down the hall, it brands itself on the brain.

Also deserving a brief mention, the multitude of peripheral characters (all of varying importance, but all wonderfully conceived): Pagliacci, Barrett's opera-loving roommate; the two orderlies who we suspect; the outright psycho who canoes across the floor and screams "Hallelujah" during Trent's racist spiel; the hilarious and even slightly frightening room full of nymphomaniacs. Fuller peoples his films with memorable characters, full of contradictions and mysteries and personality.

Not to leave out the protagonist, of course. Johnny Barrett. His languid sarcasm and tempestuous attitude (we can never tell if it's him or his feigned insanity or later, his real insanity, as the line is constantly blurred) make a nice mix, especially when confronted with an authority figure; Peter Breck (the actor) jumps from even-handed professional to sarcastic rebel to shuddering lunatic, and the performance is compelling and often hilarious.

The film is filled with its own melange of American mythology and ideology; the asylum's patients represent perversions of the American Dream, of course, but Fuller developed a parallel history to support this idea. We have Stuart's Civil War hero, and the role that Barrett adopts to get closer to him. This is reaffirmed when he speaks to Trent. Their steamboat journey together on the bench speaks of Mark Twain and the Mighty Mississippi, grass roots America and the vast folk history that stems from it. These allusions to a classic America, associated with the devastating problems represented by Fuller in the film, builds a microcosm of America; not only does Fuller point out social problems, suggesting that America is insane, he constructs a society, with a history and culture that parallels America's, for this criticism to inhabit.

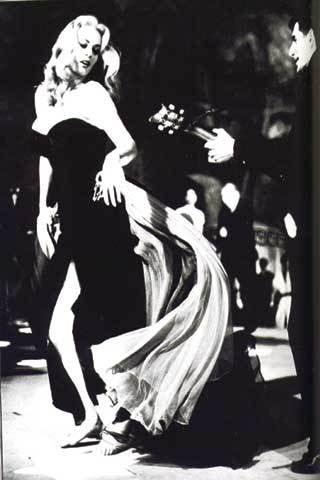

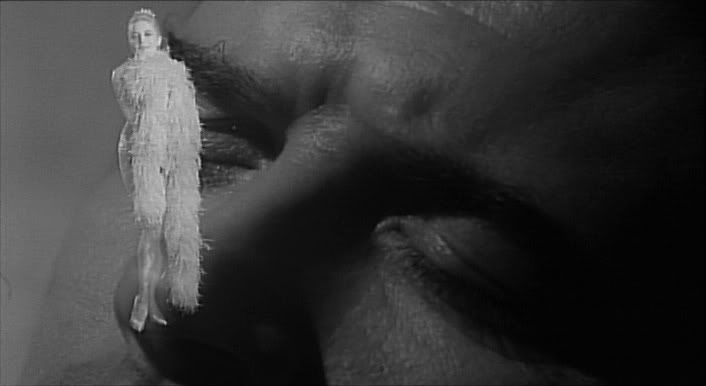

Yet we also have, at once distinct and ingrained, these dreams and visions juxtaposed with the naturalistic environment. As naturalistic as an insane asylum gets, anyway, for it's still full of operatic sleepwalkers and catatonics reaching for an invisible infinity. The dreams, those brief and memorable incursions into the minds of Barrett and his three witnesses, are what I speak of. With Barrett we have the sequences where he dreams of his girlfriend Cathy. At first, these sequences didn't do much for me, the simple layering of the girl over Barrett sleeping; but when I saw her sprawled over his shoulder, toying at his ear with her boa, it suddenly gelled. Paired with the striptease we see of her at the beginning (almost as dreamlike as Barrett's actual dreams; the dark isolation, Cathy's head consumed by the boa at the start), the scenes become almost haunting. They give credit to Barrett's decomposing mental state. A fine aural manifestation of the chaos in Barrett's life and mind occurs in one of these scenes, where Cathy's ethereal singing runs into the "la la la" of Pagliacci vocalizing some opera song (I believe from "The Barber of Seville"), creating a muddled cacophony until Cathy's song fades.

It's easy to dismiss the color sequences in the film as memorable only because they provide such a visual contrast to the otherwise black and white cinematography. For me, they're the most deeply probing and lucid moments in the film, giving another dimension to everything. They provide what one might consider the most unhindered perspective of reality we witness, something saner than sane: the clarity of vision one might have if the veil of reality could be lifted without having the comforting mist of insanity descend. It is a metaphysical clarity we see in these sequences.

The first instant of color is completely arresting: the image of a golden Buddha against a blue sky (echoes of another, earlier Fuller film, Steel Helmet). The world of the Orient, with the despairing confession of involuntary bigotry and Communist complicity as the vocal accompaniment. The shots are beautiful (although stretched by the differing aspect ratios between the b&w and color footage, which adds to the distorted atmosphere). We do not see war, or discrimination, or anything he talks about; instead, we see possibly the solitary moments of happiness he can remember, a time unaffected by American prejudice and Communist corruption.

When the color footage reappears, it is no less affecting. Trent speaks, bound to a bed, hysterical and frightened. He shrieks of men in masks, destruction, terror, while a vivid tribal dance dominates the screen. The dark-skinned dancers are masked for the ceremony. The implications are terrible and poignant, in the context of Trent's condition (and the grander social condition he represents). Men become afraid of their own cultural history, of their kinsmen and even of themselves, by the harrowing force of the white majority's will. A psychological study in the fifties or sixties had black and white children choosing whether to play with a black or a white doll; nearly all of the children picked the white doll, even the black children. The tribesmen, visually married to the Ku Klux Klan, become an embodiment of this phenomenon of displacement: the transfer of anger from the aggressor to the self.

And the last color sequence, one of pure Fullerian energy: the rushing torrent of some vast waterfall (I'd say Niagara Falls, except it might be another). This one is reminiscent of another image, where the film seems to find its title. The corridor is suddenly barren, Barrett alone and screaming in a thunderstorm contained within the building. Rain pouring down, water splashing and filling the floor, thunder screeching, lightning striking down at Barrett's convulsing form. Both these scenes shudder with uncontrollable vivacity, trembling force, and both are projections of Barrett's psyche. Interesting, that both should involve torrents of water; it's an apt metaphor for chaos, but plenty of other things are, too: landslides, volcanoes, wars. Why choose water to act as the bridge between sanity and madness? Water fascinates me, and its use here is particularly intriguing. Is Barrett being baptized into a new life, a storm of chaos followed by perpetual calm? I like to speculate, but have no answers. I can only say that Fuller's film assailed me like a thunderstorm, leaving me in a state of contemplative clarity, crisp as the scent of ozone.

Links:

Cinefile - A fine defense of Fuller as a filmmaker, in regards to this film. It's not as eloquent and simple as Truffaut's remark, but it's more disparaging to his detractors, which I fully support.

Criterion Collection essay - Definitely worth reading; short but useful.

Culturecourt - Not a great read, but worth looking into for its occasional insights that I didn't bother to highlight.