The Navigator

This is written from memory, without the film to refer to. It may be edited at a later date, once I have immediate access to the film. I recommend watching the film before reading any further.

Marriage and Domestic Space in Buster Keaton's The Navigator

The first half of The Navigator is a process of discovery by trial and error. Jean Havez, one of the film's screenwriters, describes the premise: "I want a rich boy and a rich girl who never had to lift a finger, always someone to wait on 'em - houses full of butlers, maids, valets, chauffeurs. I put these two beautiful, spoiled brats - the most helpless people in the world - adrift on a ship, all alone. A dead ship. No lights, no steam." (from Keaton, by Rudi Blesh). This description captures the essence of the couple's initial situation, but it can be reduced to one phrase: "the most helpless people in the world", although we might substitute the word 'people' with the word 'couple', to indicate their co-dependency, their pre-boat romantic history (which is relevant only as foreshadowing, since they act out their courtship on the boat), and their eventual existence as one unit in two bodies -- the married couple, two who function as one.

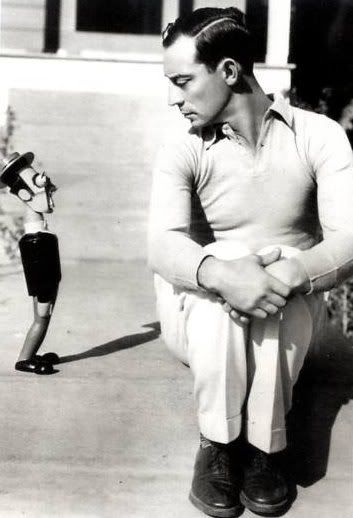

Ironically, the only picture I could find of the couple together.

First let's consider the boat. All boats, once out to sea, are isolated, making them ideal microcosms. This particular boat happens to be empty, aside from the stranded couple, which magnifies the sense of isolation. It also focuses our attention on the development of a relationship and the establishment of a domestic space, without the typical distractions (namely, other people). Since the boat is empty, its intended purpose is abandoned: no one can steer it (naming it The Navigator is pure irony), so it no longer functions as a vessel of transport. In the utilitarian sense, the boat ceases to be a boat: it looks like a boat, but it does not fulfill the purpose of a boat. Its purpose shifts under the circumstances and under the influence of the occupying couple. The boat becomes a house.

Their courtship -- their actual courtship, not Keaton's arbitrary proposal -- begins when they realize that the boat is empty. Neither knows that the other is on board. They are alone and helpless; their dependency upon other people, materially and emotionally, becomes apparent.

In reading this film, let's view their life on the boat as an existence separate from their pre-naval life, a reading I think the film encourages (the exposition serves a primarily narrative function). Upon boarding the ship they are born into a new world, alone, like Adam and Eve. They wander through the empty boat and it is absolutely clear that one man cannot handle this behemoth of a boat by himself -- it needs a crew, dozens of men rushing about. They are living in a world beyond their control. I said before that this is a process of discovery by trial and error. The first discovery they must make is each other.

The chase is Keaton's rendering of romantic pursuit: two people running circles, following the sound of anonymous footsteps (the desperation in this image increases when we consider that this is a silent film and we, the audience, cannot hear any footsteps). Their search is at first a series of displacements (one appearing where the other just left), but these are necessary failures in an attempt to meet. Displacement demonstrates that they inhabit the same space even if they lack contact. Finally they manage to find one another -- and they have, in the process of searching, familiarized themselves and the audience with the boat they inhabit. Of course, they find each other in the physical sense only, but physicality is Keaton's primary tool and he uses it to express a range of conceits.

Having found each other, they may (and must) confront their circumstances: they are stranded on the ocean on a ship they cannot control -- what is essentially a desert island scenario. During the first night we witness the extent of their inexperience: their sleeping quarters (typically a place of security) are not merely unpleasant, they are hazardous, causing physical harm to their inhabitants; the ship itself frightens them, forcing them from comfort and safety, almost as if it possesses a will of its own; in the confusion they even frighten each other (embodying the doubts and discomforts of a developing relationship). This space, the boat, is still strange to them. It is inhospitable, even hostile. They sleep, uncomfortable and frightened, like children lost in the woods.

Their troubles continue in the morning, when they attempt to make breakfast. The kitchen is industrial-sized, intended to cook for an entire crew rather than two people. The appliances and utensils dwarf the couple, and here they really do look like children, standing on tiptoes to look into a pot or holding a knife as long as their arm -- the effect is deliberate, a manifestation of their inexperience. All of their attempts at cooking in this kitchen go sour: they waste food, break dishes, and end up with hardly anything to eat. They try, and they try together -- and that is important -- but this is another misstep in their effort to become self-sufficient.

After this botched breakfast the film indicates the passage of time. This transition skips over the details of their adaptation, so we see the couple go from the height of their inexperience to a remarkable level of competence. By juxtaposing the two, Keaton not only accomplishes a certain comedic effect, he also makes a statement about their relationship by showing the extent of their progress. They have learned and matured together. They now run their lives with effortless efficiency, attending to their various responsibilities with near-automatic ease. They have transformed elements of the ship, adapting them to better suit their needs. Some parts are appropriated to construct devices in the kitchen, a predecessor to the popularity of Rube Goldberg machines in movies. They have turned the steam engine into twin bedrooms; this most clearly delineates the change in the ship's utility, from a boat meant for transport to an improvised home (although the fortified doors suggest that the two may still be afraid of what lurks outside at night). It is interesting, that they forsake the rooms meant for sleeping (which are harmful to them) and choose a place which is typically uninhabitable. They are claiming this space on their own terms. In fact, the rejection of standard domestic space is a trend throughout the film. They fail to connect on land, in their mansions; they do not become close until they enter a new world, an untraditional home. The film declares that a home must be made, not provided.

We have seen them progress through several stages of a relationship: meeting, courtship, mutual reliance, and a sort of settling down. No legal marriage takes place but the two form a bond which adheres to the spirit of marriage, mixing domesticity and affection. The humor in their slapstick misadventures defines the meta-textual heart of their relationship (they constantly get each other into trouble, but are perpetually forgiving and never attribute any blame). Our ability to laugh at their relationship represents their own ability to co-exist and to overcome.

Along with this implied marriage, they fulfill certain gender roles associated with traditional marriage. The girl does the household chores, like sweeping the deck. She is also something of a burden, often becoming the damsel in distress, especially when they confront the islanders. Keaton serves as the masculine foil: mechanic, handyman, taking on the dangerous tasks. He is the protector of his home and his partner. Of course, as characters in a comedy they not only fulfill the roles but subvert them -- Keaton especially, with his comical underwater bravado with the swordfish and the fact that he ultimately fails to keep the invading islanders off of the ship.

The islanders are an interesting and abstract element in this reading of the film. Perhaps they represent "other people", the outside world impeding upon the domestic/romantic space established by the couple (the xenophobic portrayal of the islanders becomes a metaphorical representation). The invasion is a test of their competence and of their dedication to one another; it is something they never could have faced before becoming self-reliant. And while they must abandon their home, the two stay together in spite of all adversity -- even when they have lost all else they hold close to each other, honoring some unspoken vow.