or The Sweet Life

Fellini is known for starting out as a director of Italian neo-realism, but moving from that style into much more personal and unusual works. I've seen six Fellini films, ranging from one end of the spectrum (neo-realism) to the other (balls-out fuckin' crazy). La Dolce Vita, along with La Strada (which I won't discuss but which I certainly recommend), lies somewhere in the middle of that spectrum: it still bears the weight of neo-realism, the moral obligations and the portrayal of post-war society, but it is also imbued with a magic, a wealth of strange incidents and surreal imagery, to the degree that the film nearly loses itself amongst it. The power of the film stems from the juxtaposition of these two polarized sensibilities: although surrounded by this magic, the characters in the film fail to realize its significance. But maybe that's saying too much too soon.

You should definitely watch the film before reading any further.

Nearly any essay you read about La Dolce Vita will note the significance of the first and last scenes as a sort of framing device. Both are moments where communication is obstructed in some way, first between Marcello and the suntanning girls and, at the end, between Marcello and Paola, the girl from the restaurant. Both feature the presence of some foreign object, a flying statue and a dead stingray, which is associated with Christ. It's important for me to point this out because I won't be discussing it, but I cannot ignore its significance. My exploration of the film will be through different routes. The religious and social implications of the film are fascinating, though, so I've included two essays in the links below, for anyone interested.

(I never want to suggest that my writing can be the sole supplement to any of the films discussed; if you're truly interested in learning about cinema, read everything you can get your hands on and, if there's not enough, make more.)

My approach will deal with the idea of the Sacred Moment, and how these moments are corrupted or dismissed by the characters, by their unawareness of their surroundings. This is what leads to their universal tragedy (everyone is lost, with rare exception; Marcello is merely a representative, chosen because he does not start out lost).

Before, I associated the fanciful, often surreal imagery with these Sacred Moments, but not all of the imagery is related to the idea. The statue of Christ, the children following the imaginary miracle in the rain, the seance, the perpetual presence of the swarming photographers (apparently the term paparazzi derives from the name of Marcello's photographer buddy Paparazzo): these are striking images but that does not mean they are sacred. They are strange, but they serve another purpose entirely. I allude to specific scenes, rare moments in the three hours of the film, that reflect a bastardization of truth (or what Fellini means us to understand to be truth).

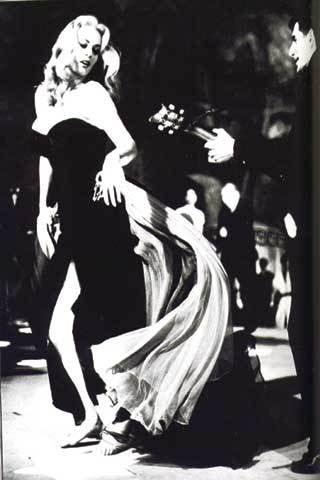

Sylvia in the fountain

Some will say that Sylvia cannot be salvation, because she is the movie star: egotistic and narcissistic, obsessed with her own glamour and fame. In a word, flawed. This is true, she very much is. But we cannot allow ourselves to view these characters as mere caricatures; they have been reduced to that, yes, but they have the potential of a full person within them and there exists the hope of being restored to that state. If they could not be saved, the film would be empty. Sylvia and Marcello are capable of saving each other, they almost reach that point, but it is their failure to sacrifice and compromise, to change in some way, that leads to the perpetuation of their isolation. (The "La Dolce Vita or La Vita Nuova?" essay below has some interesting comments about this segment of the film.)

Echoes of Nature in the Condominium

This scene does not qualify as a Sacred Moment. It does not possess the necessary magic and does not offer anyone a chance at finding meaning. The Moments I speak of represent a proximity with something beyond the redundancy of their lives. I chose this scene because it is interesting in the sense that it alludes to something spiritual (in the Wordsworthian sense that nature is spiritual), filtered through the excesses of technology so that it becomes meaningless. Fellini seems to suggest that if they abandoned their intellectual droning, left the condominium and the city and the pointless ceremony of their lives, they might be able to find some kind of salvation in nature. A proximity or true appreciation of nature and its boons might at least enhance their perception of life. But they're listening to the sounds of nature through a man-made device. It's a trifling novelty, filtering out any traces of life and inspiration. This scene speaks of their tendency to take whatever is cheap and convenient, rather than putting themselves at risk to find something worthwhile.

Speaking Through the Architecture: Invisible Confessions of Love

Perhaps (along with the restaurant with Paola) the most intimate scene in the film. Maddelena and Marcello find a moment alone at one of the innumerable, anonymous parties they attend, the one where they visit the "haunted" villa. Maddelena brings him to a room where the architecture carries sound, even whispers, from the end of a hallway to another room altogether. Maddelena confesses her love through the walls, Marcello sitting in the middle of the room, asking where she is. He reciprocates, declaring that tonight, in this moment, he feels like he needs her, needs to be close to her. Shortly afterward she's kissing another man while he's left calling for her, with no idea about where she is.

Let's not get into the multitude of meanings and interpretations we could find in this scene. I'll leave those to you, or whoever else wants to analyze it. Instead, let's assume that Marcello (if not Maddelena; she seems genuine, to have a spark of honesty, but she's too far gone) really meant what he said. Let's assume that, for that moment, he wanted her and needed her and loved her. Or at the very least, that he felt like he needed to love her. I get the sense that Marcello and Maddelena are desperately close here; true, it is significant that she's in another room, that she can only confess to him invisibly. But Marcello, he wants to see her, asks where she is, wonders if something might become of this talk. She's lost, but he's not so far gone yet. It feels like in another time and place these distant whispers might have become actions, and thus connections and emotions and devotions. That doesn't happen. The image of Marcello moving about aimless and alone, the sought-after Maddelena kissing another man, is tragic. What could have been a beautiful moment in a different life is a farce for them.

Let's not get into the multitude of meanings and interpretations we could find in this scene. I'll leave those to you, or whoever else wants to analyze it. Instead, let's assume that Marcello (if not Maddelena; she seems genuine, to have a spark of honesty, but she's too far gone) really meant what he said. Let's assume that, for that moment, he wanted her and needed her and loved her. Or at the very least, that he felt like he needed to love her. I get the sense that Marcello and Maddelena are desperately close here; true, it is significant that she's in another room, that she can only confess to him invisibly. But Marcello, he wants to see her, asks where she is, wonders if something might become of this talk. She's lost, but he's not so far gone yet. It feels like in another time and place these distant whispers might have become actions, and thus connections and emotions and devotions. That doesn't happen. The image of Marcello moving about aimless and alone, the sought-after Maddelena kissing another man, is tragic. What could have been a beautiful moment in a different life is a farce for them.

Paola

This girl appears twice in the course of the film, once around the middle and once at the very end. What Paola signifies, in relation to Marcello, is more or less clear: a redemptive force, something akin to the Sacred Moments I've been dwelling on. The difference lies in the characters with which Marcello engages. Paola is, we presume, an innocent of sorts, whereas the other characters Marcello interacts with all exhibit a level of corruption comparable to his own. Paola doesn't qualify as a Sacred Moment, one existing as a perpetual occurrence, embodied in an individual. The Sacred Moment can only be just that, a moment, where circumstance leads Marcello to an opportunity with redemptive or restorative potential, granted that certain decisions are made, or rather, a certain perspective adopted. Only one scene with Paola provides this for Marcello, the scene in the restaurant. Her brief appearance at the end signifies something else entirely: it indicates the severity of Marcello's loss, that he's stooped to a point beyond redemption, where he can no longer even hear her.

The minutes spent together in the restaurant are the only in the film that one could actually describe as sweet. It's simplistic and unremarkable, yes, but consider the vapid world of wealth and spectacle that Marcello usually inhabits. The girl is pretty, but not exotic or gorgeous like Sylvia or Maddelena or even Emma. These idle moments of simple conversation, platonic compliments, and radio music give a context for warmth and happiness in the film. Marcello has this, fleetingly, although he obviously cannot appreciate its importance. Let's dismiss the idea of Marcello's genuine interest in literature as an avenue to meaning; note, in this scene, how he does not manage to write anything, even with his typewriter in front of him. He doesn't need to. The distractions of the world soon impede upon this paradise, though; one wonders whether such tranquility can ever be permanent.

The minutes spent together in the restaurant are the only in the film that one could actually describe as sweet. It's simplistic and unremarkable, yes, but consider the vapid world of wealth and spectacle that Marcello usually inhabits. The girl is pretty, but not exotic or gorgeous like Sylvia or Maddelena or even Emma. These idle moments of simple conversation, platonic compliments, and radio music give a context for warmth and happiness in the film. Marcello has this, fleetingly, although he obviously cannot appreciate its importance. Let's dismiss the idea of Marcello's genuine interest in literature as an avenue to meaning; note, in this scene, how he does not manage to write anything, even with his typewriter in front of him. He doesn't need to. The distractions of the world soon impede upon this paradise, though; one wonders whether such tranquility can ever be permanent.

Other scenes in the film suggest an urge for the Sacred Moment, some significant connection with another human. These attempts, often instigated by Marcello, tend to fail. When Marcello brings Emma to the hospital after her suicide attempt, how earnestly he talks to her, only to call Maddelena afterward (who is asleep, who does not, one might say cannot, respond). When Marcello's father comes to town looking for a good time, the desperation with which Marcello tries to bond with him (an absent figure in childhood). This situation, too, ends miserably.

It seems that Marcello, from the start, is a man doomed to find no meaning. He is such a passive host, merely moving to where the flow of the grand party takes him. When Sylvia climbs into the fountain, he follows her reluctantly. When his girlfriend takes pills, he brings her to the hospital; when they argue, he picks her up in the morning. The women in his life guide him around without leading him anyplace, and he is willing to let this happen (only one woman, the girl from the cafe, does not force him someplace and it is probably because she does not force him that he cannot follow her). He seems to be on a pursuit for meaning, but it is clear he will fail. Any fleeting interest he takes, be it literature, religion, sex, he takes because others indulge; the only course he knows to happiness could be through others. He writes literature because others seem to think it will lead to meaning, not because he's convinced of the truth and power of literature itself. Everything ends in passive defeat. He seems so uncertain, so reliant on the pursuits of others, that even his pursuit of meaning seems like an imitation. He only searches for meaning because others search for meaning.

That is why he's doomed to fail.

Links:

The following two links are essays written about the film, the second in response to the first. Both are very interesting, and worth reading if you have the time. I think the arguments in the response are generally stronger and more observant, but they're both perceptive.

They're also both on JSTOR, so you'll need access to that server to read them.

"La Dolce Vita: Twentieth-Century Man?"

"La Dolce Vita or La Vita Nuova?"

This article is long and only haphazardly insightful, but it has its moments. If you just want to glance through it, I recommend reading footnote 21 and the section of the essay to which it corresponds.